I’ve been marinating on “blame the system, not the individual,” a concept I touched on in an earlier post, “Natural Beauty.”

The model, Emily Ratajkowski, has always bothered me in a way that I could never quite articulate. Now I have the words for it after reading Haley Nahman’s newsletter, “Maybe Baby.” In her piece titled, “#24: The Emily Ratajkowski effect,” she offers an excellent written critique of choice feminism, and a thought-provoking discussion in her podcast episode, "Unpacking Emrata's feminism w/ Mallory Rice." The crux of the issue is this: can you critique a system that you are actively perpetuating? Nahman and I think not.

I tend to be a very binary/black-and-white thinker. I just got a new therapist and we are going to work through a DBT (Dialectical behavior therapy) workbook. A dialectic is when two seemingly conflicting things are true at the same time. Per Wikipedia,

“Dialectic, also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to establish the truth through reasoned argumentation. Dialectic resembles debate, but the concept excludes subjective elements such as emotional appeal and rhetoric.”

DBT appeals to me because I want to spend more time in the middle, not in the extremes. Before I had words for this kind of thinking, I had been trying to sit with the notion that “two things can be true.” A few months ago, I said this to my friend who recently had a kid when she was feeling conflicted about the distribution of parental duties. I told her that she is allowed to feel tired and annoyed at her husband for not pulling his weight on baby duty, even though he is working tirelessly to “bring home the bacon” for their family. You can hold opposing views. I am trying to get comfortable with this new line of thinking.

But can I apply this same logic to Emily Ratajkowski? Is she allowed to point the finger at the corruption of the modeling industry while still bringing home a large modeling paycheck? This feels less dialectical and more hypocritical to me.

Nahman’s newsletter was written in response to Ratajkowski’s piece, “Buying Myself Back,” in which the model doubled down on choice feminism. Per Nahman, this means “any choice a woman makes is inherently feminist, and any criticism of those choices is therefore anti-feminist.” Nahman brilliantly asserts that Ratajkowski’s piece lacks depth:

“There is no broadening of her point to include people other than herself; there is no genuine analysis of the complexity of modeling (a profession that is literally defined by selling one’s image) and female agency. There is no mention of actual copyright law, or the photographers and makeup artists and producers who helped create the image that she posted on her Instagram, who were also exploited by Richard Prince. The most interesting parts, where she paints herself as complicit in some way, are never further unpacked, and so seem included for extra honesty credit. It’s not that I think she elided meaningful criticism in bad faith, or on purpose—I think she did so compulsively, as an expression of her (and many people’s) general approach to systemic change, which is to assume that by simply calling out a problem, or exploiting it in her favor, she takes away its power.”

What bothers me about Ratajkowski is that she refuses to acknowledge her inherent contradictions. She wants to be viewed as a victim and not a perpetrator, and in many cases this is true. But two things can be true. She is both. Life is messy. It doesn’t fit into neat boxes the way our brains would prefer. People are flawed. I desperately want Ratajkowski to acknowledge this fact.

Lately, I have noticed that those close to me shut down when I ask them to consider opposing viewpoints. For instance, a friend and I are excited about the new “Barbie” movie because we both love Greta Gerwig. I recently discovered Jessica DeFino’s newsletter, "The Unpublishable," which offers scathing critiques of the beauty industry. DeFino wrote a piece that caught my eye called “'Barbie' Will Be Bad For Beauty Culture.” Her words also articulated a feeling I had but couldn’t put a finger on. Why is Gerwig choosing to reinvigorate our obsession with Barbie when Barbie is so clearly a symbol of sexism and female repression? I sent this article to my friend and she refused to read it. She didn’t want to engage in dialectical discourse. I was crestfallen. This friend staunchly supports choice feminism, so I guess I need to know my audience. DeFino writes:

“Based on this synopsis of the plot…’After being expelled from ‘Barbieland’ for being a less-than-perfect doll, Barbie sets off for the human world to find true happiness.’…it seems writer and director Greta Gerwig intends to subvert everything the Mattel toy symbolizes in American culture: conformity, compliance, doll-like perfection, the objectification of women. It’s more fulfilling to be an imperfect human than a perfect doll! Being real is the only way to be happy! That sort of thing. However! Much like we saw with Don’t Worry Darling and Blonde, you cannot separate the politics of Barbie from the beauty standards of Barbie. The story may promote being an imperfect human, but the visuals still promote a stifling standard of aesthetic perfection.”

“You cannot separate the politics of Barbie from the beauty standards of Barbie.” Just as Ratajkowski cannot separate the politics of modeling from the beauty standards of modeling. DeFino continues,

“I just don’t think you can effectively challenge an oppressive ideology and adopt its aesthetics. That’s not how aesthetic communication works!! The movie may be a “feminist” reclamation of the Barbie narrative in spirit, but its material effect on society looks the same as subjugation. Blonder, tanner, thinner, smoother, static, plastic.”

In “When I was an influencer,” Nahman grapples with the moral messiness of promoting sponsored content,

“Over time though, it became clear to me that I was using my social position at a feminist-leaning website to sell shit to women that they didn’t need, sometimes in direct opposition to the ideas I hoped to explore in my writing.”

Prompted by this reader’s response, Nahman dives deeper into the idea of “selling out” in her podcast, “The morality of the influencer.”

Hi Haley! I'm trying to work through some of my own thoughts on fame/influencer culture and sponcon and have been thinking a lot about the costs associated with doing good when many societal structures seem to incentivize greed, ambition in all its forms...aka doing bad. This prompted me to reread your “When I was an influencer” newsletter and while I admire your dedication to your ideals, and often turn to you for clarity and understanding, my unsolicited POV is: I do wonder if you're being too hard on yourself?

To me, this all ties back to my career struggle. Knowing that I feel a deep need to “make the world a better place,” can I ever go back to the corporate/tech world? It feels like selling out my values. Does this mean that I have to “assume a vow of poverty” (my mother’s words) and work in the non-profit space to feel aligned with my morals? I know it’s not that cut and dry but why does it feel this way?

In her podcast, Nahman examines the ugliness of our culture’s current mantra, “get your bag.”

“But what is selling out? To me, I think there's a few different ways to define it. I think it's selling out your values. So like, you know, choosing like financial incentives over creative ones or aligning yourself with like industry over community, with brands, over people.

If you're coming up with like elaborate reasons that you should be able to like get your bag at the expense of other people I think that's selling out like I think I think it is That's why i've never liked to get your bag because get your bag is like fuck the like judgment of other people Just like get your money implied and get your bag is like you shouldn't have to worry about the um, Sort of collective the consequences on the collective if it means like you yourself will get to succeed It's just to me. I'm like

Why would we want to have that be our ultimate value? Get your bag. It's very American. It's very individualistic. I actually think it's really good for us to be communally minded. I think it's great to think about how makeup affects everybody. People, especially on the margins of society. I think it's important to think about those things. And I'm not saying you should never do anything for yourself. You gotta fucking live your life. But...

Do I think it's good to live by a statement such as get your bag that embodies like always choosing yourself over the collective? Like no, I think that sucks and I do think that's selling out. And you know, maybe we all sell out here and there in our lives. I think being a sellout is like making your livelihood around that particular compromise. And I think that that's true, I think it's more true for people who are like conscious that they're doing it.

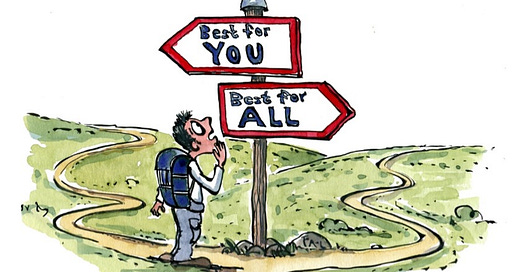

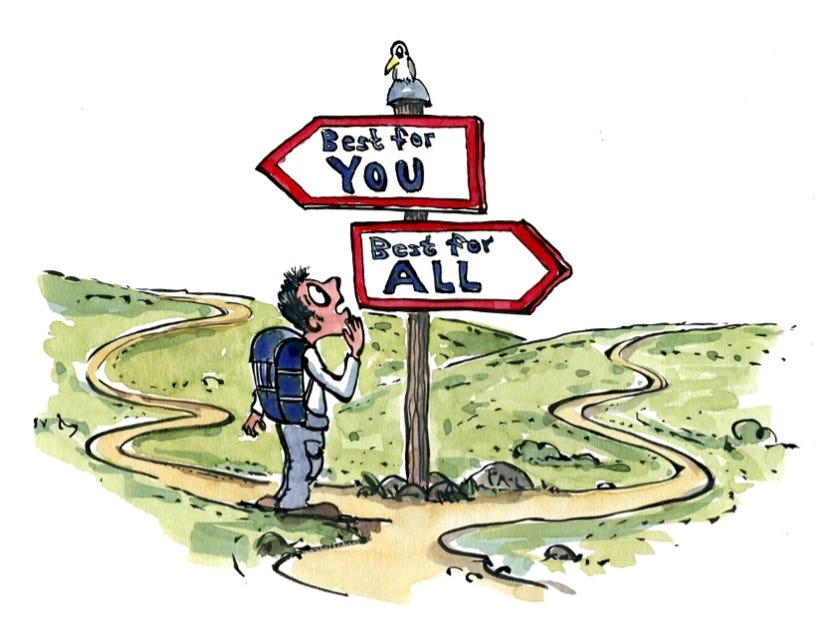

I don’t have any clear answers. I know I’ll be wrestling with these ideas for a long time. I am often reminded of the tragedy of the commons, which I learned about in an environmental science class I took in high school. Per Wikipedia,

“According to the concept, if numerous independent individuals should enjoy unfettered access to a finite, valuable resource e.g. a pasture, they will tend to over-use it, and may end up by destroying its value altogether.”

What are your thoughts on choice feminism? Can you challenge a system while also perpetuating it? What is selling out? What contradictions are you willing to uphold in your own life? How do you justify them? Does making an individual choice inherently harm the collective?

—